Campus mental health is dominated by the narrative of crisis, painting a dire picture of rampant and ever-increasing anxiety and depression among students. This unidimensional portrayal does not capture the entire spectrum of student experiences, especially student resilience and capacity to thrive in the face of ongoing threat, ambiguity, and adversity. It is time to deconstruct the singular “campus on fire” narrative and consider more complex and nuanced understandings of campus mental health.

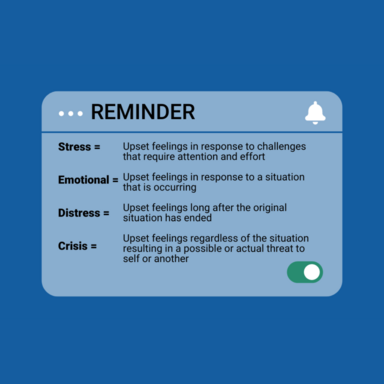

Let’s define our focus. We hear of epidemic levels of anxiety and depression. What we know, however, is that student emotion falls across a continuum. The gauge below provides the various positions students can be emotionally:

Stress- Upset feelings in response to challenges that require attention and effort.

"I am feeling overwhelmed because I have a big project due tomorrow.”

Emotionality - Upset feelings in response to a situation that is occurring.

“I am really upset and sad because I just found out I got bad grades this semester.”

Distress (where anxiety and depression locate) - Upset feelings long after the original situation has ended.

“I got bad reviews at work. I never do well. It’s not worth trying anymore. I have been so angry and disappointed with myself these past months.”

Crisis - Upset feelings regardless of the situation that result in possible or actual threat to self or another.

“I give up. I see no purpose or point. I don’t care anymore. This is the end.”

While some students live episodically or chronically managing symptoms of diagnosable anxiety and depression, the majority of our students in the majority of situations are managing stress and emotionality. Being upset about upsetting things is not a mental health crisis it is a reasonable response to unreasonable things.

It is crucial to acknowledge external factors that contribute to students’ emotionality. The current moment is fraught with a global pandemic, political turbulence, wars, and bottomless digital age challenges. While these factors exacerbate emotionality, they do not necessarily translate into a surge of clinical mental health problems like depression and anxiety. One can feel stress about stressful things without having diagnosable anxiety. Likewise, one can feel sadness about sad things and not have diagnosable depression.

As Denison University President, Adam Weinberg stated,

“We need to assure students that mental health challenges are not a personal failing but a reasonable response to a challenging historical moment” (Weinberg, 2022).

The assumption that emotional responses to external stressors invariably are mental health crises does not support the complex interplay between students’ individual grit and resilience and the impact of environmental factors beyond most students’ control.

Contrary to the crisis-centric view, research (Volstad et al., 2020) indicates that a significant portion of the student population adapts and copes with the transitions and stressors that are part and parcel of campus life. While it’s undeniable that mental health issues exist and must be addressed, most students are successfully navigating these challenges.

The need for a balanced perspective on mental health that acknowledges both challenges and successes is vital. How we frame the current emotional temperature on campus impacts how our students frame this for themselves. The New York Times (Saxbe, 2023) noted that what can be considered “problems of living,” or “normative worries” have been reframed for America’s adolescents as “mental health crises.” Saxbe quotes Dr. Lucy Foulkes, an Oxford University psychologist, who noted that framing the struggles of life as mental health crises has dictated how “people view themselves in ways that become self-fulfilling” and “encourages people to view everyday challenges as insurmountable.”

Empowering Students to Flourish

The National College Health Assessment (NCHA) (2023) publishes data annually noting that students struggle with significant mental health and well-being challenges, including distress-level concerns. The NCHA also publishes data noting that the majority of the same students also see themselves as flourishing, reminding us that even when we struggle, we can also be doing well.

By shifting the prevalent campus narrative to recognize the whole range of student experiences, we better frame more supportive and realistic conversations about mental health.

This involves adjusting our approaches to include empowerment, skill-building, and refilling regularly tapped wells of resilience. By doing so, we prepare students to manage the present and ongoing challenges of being in the world while proportionally supporting the foundational assumption that life has struggles. In deconstructing the campus mental health crisis narrative, we must stay mindful not to minimize student struggles and highlight their strengths and the positive steps many have taken towards their well-being. A balanced dialogue acknowledges inherent difficulties while celebrating growth and perseverance through adversity.

Our students are remarkable, let’s remind them, expect this of them, and remember that bad things feel badly, and is okay. And when it does become distress, resources can provide support.

In closing, let us remember: How we frame the current emotional temperature on campus impacts how our students frame this for themselves.